Conferences

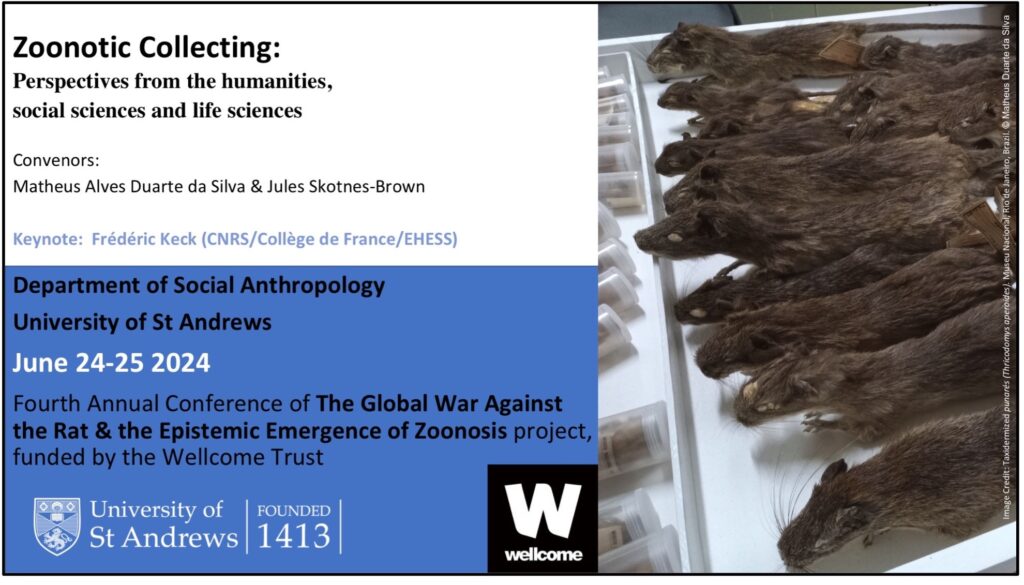

Zoonotic Collecting: Perspectives from the Humanities, Social Sciences and Life Sciences.

June 24-25 2024

The 4th annual conference of The Global War Against the Rat and the Epistemic Emergence of Zoonosis project. The conference is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Collections have played an important role in scientific understandings of diseases and their control in past and present, from anatomical collections assembled to study the natural history and taxonomies of human diseases, to zoological collections of disease reservoirs, to collections of microorganisms for pandemic preparedness, to teaching collections for the education of doctors, veterinarians, and lay publics. Extracting specimens, taxidermizing these, creating models and displaying them have been particularly important to the medical sciences. Natural history museums, for example, have been instrumental in the science of disease ecology and the control of zoonotic diseases. In the past, they have served as key sites for the identification and cataloguing of animals deemed to be vectors and reservoirs of diseases, and for charting their ecological relations with the environment. In the present, microbes are often collected and preserved in laboratories for the study of infectious diseases and the improvement of human, animal, and plant health, or, more sinisterly, the development of bioweapons.

Simultaneously, outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics have played a critical, if underappreciated, role in the history of collecting. Outbreaks of zoonotic diseases provided zoologists with unprecedented funding and resources to collect rodents, mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, and microorganisms. Widespread campaigns against disease vectors likewise mobilized civilians to kill and send in thousands of verminous animals for inspection at medical institutions and museums, in many cases furnishing institutions with large collections. In other cases, doctors and epidemiologists used the resources provided by public health campaigns to make vast ethnographic collections of human culture in the course of their duties. Finally, specimen collecting itself has, at times, provoked fears that the act of capturing and transporting specimens might result in outbreaks of zoonotic disease, sparking new biosecurity and biopolitical measures.

Bringing together perspectives from the history and anthropology of medicine, museum studies, animal studies, ecology, and other disciplines, this conference seeks to understand the relationships between collecting (broadly construed) and zoonosis. In so doing, it aims to chart how collecting has been linked with medical and health questions; the material, epistemological, and political lives of medical collections; and how collecting in times of outbreaks, epidemics, and even pandemics has shaped the lives of humans, plants, microbes, animals, and insects.

Epizootics Beyond the Farm: Historical and Ethnographic Approaches

Invasive Species and Shifting Disease Ecologies: Perspectives from the Humanities and the Social Sciences

Reframing Disease Reservoirs: Histories & Ethnographies of Pathogens & Pestilence